Labour migration and displacement and replacement of native workers in the European Union: Some lessons from the past

Download dit artikel als pdf-bestand

- The analysis of the eighteenth-century Dutch maritime labour market yields insights into the effects of large-scale labour migration on a recipient economy

- This paper shows that long-term, large-scale labour market shifts can have an impact on the receiving economy

- The replacement of large numbers of native-born workers with labour migrants may make an economy vulnerable to changes on the supply side, particularly during periods of economic stagnation

- The historical case study presented here shows that the economic catch-up of traditional labour-shedding nations with the main attracting cores can lead to a change in the dynamics of the labour market

- In the case of the eighteenth-century Dutch labour market a change in the dynamics of the labour market did not lower immigration levels, but it did lead to a different pattern of migratory behaviour

- In the eighteenth-century Netherlands, labour migrants were at first a group characterised by relatively high skill levels and equal numbers of long-term and temporary workers but increasingly became a transient labour force of temporary migrants with subpar levels of human capital

Introduction

The expansion in May 2004 of the European Union (EU) brought in ten new member states (NMS): eight Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary and Slovenia) and two from the Mediterranean (Cyprus and Malta). Although some countries, including the Netherlands, imposed restrictions (albeit temporary) on migrant labourers from the CEE nations, the opening of the borders led to an increase in the number of people migrating from Eastern to Western Europe. The Netherlands experienced its largest influx after 2007, the year it fully opened its borders for NMS workers. Mainly as a result of the migration from the NMS between 2001 and 2011, the share of foreigners among workers in the Netherlands nearly doubled, growing from 4 to 7.7 per cent.

SEO Economisch Onderzoek (SEO), an independent Dutch think tank, published a report at the end of 2014 on the economic effects of the increased migration from CEE countries. This study, commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, concluded that the rise in immigrant workers after 2007 had led to important labour-market shifts; it had led to replacement and displacement of native-born workers. Replacement is a process in which foreign-born migrants take positions that had previously been held by native-born workers. The prior Dutch worker may have retired, changed occupation (i.e., moved to a different employment sector) or have became self-employed (in Dutch: zzp-er). Crucially, this process is voluntary or – as with retirement – natural. When displacement occurs, by contrast, native-born workers are pushed out, usually due to unfair competition, i.e., foreign workers are paid less, illegally. SEO found that not only had replacement occurred on a large scale; there was displacement as well, but only on a sectoral level. In sectors such as construction, horticulture and transport, Dutch workers indeed faced unequal or unfair competition, making native-born workers less attractive to employers. Individuals were being forced out – and not because of the labour market’s natural evolution or because employees had left a sector voluntarily.

These results are important for a number of reasons. First, they raise several policy questions, in particular regarding the legislative framework for foreign labour participation and the extent to which competition between foreign- and native-born workers may be unequal or even unfair. Moreover, though in most cases Dutch workers were not forced into unemployment, a labour-market shift tending towards the domination of an entire sector by non-native-born workers may still be considered undesirable. The negative consequences of such a trend have usually been identified on the local level: in some cases (highlighted in the media) a high concentration of labour migrants has been accompanied by poor living conditions and increased levels of anti-social behaviour. Finally, the issue of replacement and displacement is also relevant in light of the ongoing debate about the EU’s future expansion. The fact that the recent and current CEE migrations led only to displacement on a macro-level does not necessarily imply that there may not be negative consequences in the future. Nor are the broader economic consequences of shifts in the overall labour market (including replacement and displacement) fully understood.

The intrinsic problem in assessing the more long-term economic effects of CEE migration lies in its being a relatively recent development, and a phenomenon that is quite distinct from the guest-worker migrations from (mainly) Mediterranean Europe during the 1970s. Therefore, little can be said about its lasting consequences. Useable data is available only through 2011, while, for instance, the financial crisis only really hit the Netherlands hard in 2009. In other words, as we only have data from about two years after the 2009 crash, it is difficult to predict the mid-to-long-term effects of CEE labour migrations. To discuss certain possible long-term effects of the recent migrations from the CEE and in particular the effects of displacement and replacement, I will focus in this paper on developments in the eighteenth-century maritime sector: a key, extremely well-documented segment of the Dutch transport sector, and an area in which labour migration played an important role. The data behind the case study is derived from a survey of around fifteen thousand workers and covers two periods: the first from 1702 to 1712, the second between 1777 and 1801.

The historical background

The eighteenth-century maritime labour market can serve as a historical laboratory to study the effects of labour market change. Admittedly, there are distinct differences between the modern and historical Dutch labour markets, most notably the lack of policy instruments available to (central) authorities in the latter. However, similarities in immigration levels, economic trends and labour characteristics with our contemporary situation, in combination with the availability of data for a lengthy period of time, make the eighteenth-century labour market a very suitable and relevant comparative case, and can help identify the possible consequences of large-scale immigration on a recipient labour market.

As in the twenty-first century, immigration levels in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Netherlands were high. Figure 1 below graphs the share of resident migrants in the Netherlands between 1600 and 2000. It shows that the relative number of immigrants in the Netherlands reached its highpoint during the seventeenth century, coinciding with what is generally referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. Interestingly, the immigration peak around 1650 was surpassed only in the late twentieth century. Figure 1 also shows that during the eighteenth century, which was characterised by overall economic stagnation, the number of resident migrants slowly dwindled. It is, however, important to note what is not visible here. As the graph depicts only resident migrants and thus excludes those not resident in the Netherlands (i.e., temporary migrants), the graph underestimates overall mobility. As will become clear below, as in the first decade of the twenty-first century, temporary migration became much more important during the eighteenth century than it had been in previous periods.

The maritime sector was an important segment of the Dutch labour market; during the eighteenth century around 15 per cent of the male working-age population of the coastal provinces was involved in shipping. Luckily, there is abundant data available for this sector. Countering the overall economic trend, the maritime sector enjoyed a period of expansion: between 1700 and 1800 it increased by about 27 per cent. Because of a slowly growing Dutch population, immigration was essential to the sector. Like CEE migration to post-2007 Netherlands, labour mobility in the eighteenth-century maritime sector was facilitated by the absence of restrictions on foreign workers and was further stimulated by large differences in wage levels between the Netherlands and the migrants’ countries of origin. During the course of the eighteenth century the percentage of labour migrants working in the maritime sector increased sharply. Around 1700 about 32 per cent of the unskilled and semi-skilled workforce consisted of foreigners; in 1800 this figure had risen to 64 per cent.

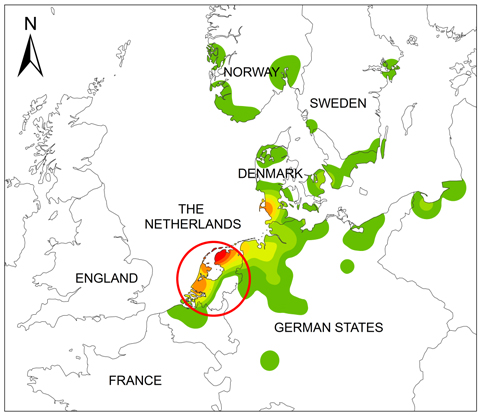

Although the Netherlands in both the current and historical cases drew most of its labour migrants from Europe, recruitment patterns differ slightly. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries most labour migrants came not from Poland (as is the case today) but from Germany and Scandinavia. The same preponderance of Germans and Scandinavians also applies to the workforce in the eighteenth-century transport sector, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2, which depicts the key regions of origin for workers in the Dutch maritime sector, shows that employers attracted workers mainly from northwestern Europe, in particular from northern Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Of all temporary migrant workers in 1700, 48 per cent were born in Germany; in 1800 this percentage was even higher: 61 per cent. As for long-term migrants, the share of Germans was 24 per cent in 1700 and 54 per cent in 1800. The second largest group of labour migrants in the Dutch maritime labour market consisted of workers from the Scandinavian countries: temporary workers accounted for 37 per cent of these workers in 1700 and 23 per cent in 1800; 22 per cent of all long-term migrants in 1700, and 29 per cent in 1800, came from the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

In terms of their age characteristics, eighteenth-century labour migrants and native-born workers did not substantially differ from their twenty-first-century peers. The data show that like today’s CEE workers in the Netherlands, temporary migrants were then mainly between 19 and 29 years of age; long-term migrants tended to be in the 24–35 range. However, in contrast to the modern case, there is no evidence of large wage differences between native- and foreign-born workers in the historical data. What the data do show is that the labour market was highly segmented – also not unlike the modern labour market – with native-born workers dominating the relatively skilled and well-paid jobs; migrants were overrepresented in the segment consisting of lower-paid and unskilled or semi-skilled occupations. Indeed, the historical data show that Dutch workers dominated the upper segment, though their share fell over time (from 80 per cent in 1700 to 60 per cent in 1800). As I mentioned earlier, even more substantial changes can be traced in the lower segment. In 1700 Dutch labourers made up the majority of unskilled workers, but in 1800 there were more migrants than Dutch workers among the lower-ranked jobs: 64 per cent were of foreign origin (21 per cent consisted of long-term migrants, 43 per cent were temporary migrants).

Displacement and replacement

In contrast to the modern case, where Dutch workers in some sectors face unequal or unfair competition with foreign-born workers, often because of employers’ non-compliance with labour laws, there is no evidence of macro-level displacement in the historical case. All available evidence for the historical maritime labour market suggests a level playing field for native- and foreign-born workers. Most importantly, the wage levels of foreign and Dutch workers were identical. Although it cannot be ruled out that foreign workers were paid less, illegally, it is unlikely that this happened on a large scale. Can we therefore conclude that the increasing influx of foreign workers yielded no negative effects? I would argue that growing immigration from Germany and Scandinavia had certain adverse consequences but displacement was not the key problem. The root of the negative effects lies in the large-scale replacement of Dutch workers. To explain why the shift towards a labour market dominated by foreigners exerted a detrimental economic effect, it is first necessary to understand the extent of the changes that occurred in the eighteenth-century labour market.

Earlier, we saw that the post-2007 labour market exhibited a macro-micro paradox involving a large-scale sectoral displacement of native-born workers, though there was no indication that individuals were actually being forced into unemployment on a large scale. Given that evidence for macro displacement is lacking, might there be evidence for a reversed macro-micro paradox, with no evidence for macro-level displacement but proof that individual workers were being forced into unwanted idleness? For the historical case study it is not easy to establish what the effect of displacement was on individuals, who are difficult to trace once outside the sector. However, most evidence suggests that in this era the negative micro-effects were likely also limited. Unemployment, though not uncommon in the eighteenth-century Netherlands, was mainly confined to the cities – not the usual recruitment areas for Dutch maritime workers, who came mainly from rural parts of the provinces of Holland and Friesland. It is more likely that, as suggested by De Vries (1994), Dutch maritime workers voluntarily switched to other sectors of the economy, particularly those regarded as being more secure.

On their own, labour-market shifts need not be detrimental for the segment of the economy they occur in. If language skills are not an important prerequisite for the labour process, from an economic viewpoint, foreign- and native-born workers are largely interchangeable; it therefore matters little whether foreign labour participation is at, say, 80 or 10 per cent. The historical data demonstrate, however, that under certain circumstances such labour market shifts can exert negative effects on the sector and the economy at large.

The negative impact of replacement

The key problem in the eighteenth century labour market was that the absolute and relative increases of long-term and in particular temporary workers were accompanied by a deterioration in the skill levels that these migrants brought to their tasks. In other words, the negative economic effect of the labour market shift was not caused by Dutch workers being replaced by migrants; what mattered is that they were replaced by workers with lower skill levels, which in turn lowered the overall human capital stock in the sector. A recent study by Van Lottum and Van Zanden (2014), which used numeracy and literacy levels as human capital proxies, showed that in the maritime sector these human capital indicators correlated with productivity levels. This means that the influx of foreign workers had a dampening effect on productivity, and thus on the sector’s economic performance. The Netherlands’ increasing reliance on a foreign labour force meant that this development had a substantial impact.

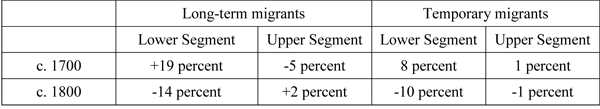

Not all segments of the sector experienced the negative effects of migration. In the upper segment of the eighteenth-century labour market – the segment consisting of skilled workers – immigration appears to have had no real adverse effects on human capital levels. This is indicated in Figure 3 below, which shows the skill differential (based on literacy levels) between the two migrant categories and Dutch workers.

The figures for the upper segment indeed show low skill differentials and very little change over time. Skill levels of both temporary and long-term migrants were more or less on par with those of Dutch workers in 1700 and 1800, and even the literacy level of upper-segment workers in 1700 is only 5% lower than that of their Dutch peers.

In the lower segment of the labour market – the segment comprising semi-skilled or unskilled workers – the figures show a different pattern. Whereas in 1700 skill levels of both temporary and long-term migrants where higher than those of Dutch workers (8 and 19 per cent higher, respectively), thus contributing to overall human capital levels in the sector, by 1800 this skills surplus had become a deficit. Although skill levels of all groups grew over time, the increase among Dutch-born workers outstripped that of all migrant groups. In 1800 both long-term and temporary migrants in the sector’s lower segment had much lower skill levels than their Dutch peers, respectively 14 and 10 per cent lower.

To draw lessons from these phenomena it is necessary to understand what caused the deterioration in migrant workers’ skill levels. The root of the problem lay in the long-term stagnation of the Dutch economy and the simultaneous catch-up of the traditional labour-supplying countries. Slowly but surely, the economies from which the Netherlands drew most its labour began to expand – and the Dutch economy’s relative stagnation resulted in shrinking wage differentials between the Netherlands and Germany/Scandinavia (Van Lottum, 2011). Although wage levels had not yet fully converged by the end of the eighteenth century, the potentially smaller reward for migrating, in combination with growing opportunities at home, changed the dynamics of the international labour market. Whereas since the seventeenth century migrating to the Dutch Republic had been an obvious option for those seeking economic betterment, increasingly the Netherlands had to compete for workers with employers from the traditional sending economies.

Importantly, we saw earlier that the increased competition did not lead to a drop in immigration from these countries to the Netherlands. Demand in the Netherlands was high, there remained a labour surplus in the sending countries, and wage differentials, while smaller, still existed. However, growing competition did change the character of the labour supply. First, increased competition led to growth in temporary workers. Because there were now more opportunities for potential economic migrants, fewer of them chose to settle abroad, and more and more migrants travelled back and forth between home and afar, picking out the best opportunities. Second, because the Netherlands was indeed no longer the prime centre of attraction for potential migrants (workers), from the perspective of the Netherlands the labour supply became less elastic. In practice, this meant that Dutch employers found it more difficult to get the right migrant workers, and even if they did, these labourers were difficult to retain because of the transient character of the labour supply.

Conclusions: Lessons from the past

Analysis of the Dutch maritime labour market in the eighteenth century yields some relevant insights into the effects of large-scale labour migration on a recipient economy. It shows that even in the absence of displacement, long-term, large-scale labour market shifts can have an impact on the receiving economy. The findings presented in this paper suggest that the replacement of large numbers of native-born workers with migrant labourers may make an economy vulnerable to changes on the supply side, in particular when this happens in periods of economic stagnation. The case study showed that the economic catch-up of traditional labour-shedding nations with the main attracting cores can lead to a change in the dynamics of the labour market. In the case of the historical Dutch labour market this did not include the lowering of immigration levels, but it did lead to a different pattern of migratory behaviour. In the Netherlands, the population of labour migrants in the Netherlands were at first a group characterised by relatively high skill levels and equal numbers of long-term and temporary migrants but increasingly became a transient labour force of temporary migrants with subpar levels of human capital.

Should a scenario like the one sketched above become a present-day reality, the current EU framework provides few policy measures that can be taken to counteract it. Indeed, the right of freedom of movement for workers prohibits the selection of migrants at the border, a measure that would limit the influx of unskilled or ‘under-skilled’ workers. However, even if this were possible, it may be unwise to do so within the current regulation. With low natural growth levels in most EU countries and the continuing need and potential for sectors to expand (even in times of economic stagnation), labour migration remains a way of importing an important production factor. Diminishing the influx, even if the economic match may not be optimal, may have larger adverse effects. There are, however, opportunities available for national governments and employers to diminish or even prevent displacement or replacement that causes long-term economic damage. First, further measures should be taken to tackle unequal and unfair competition between native- and foreign-born workers, thus creating a level playing field and ensuring that Dutch workers are not forced into unemployment. Second, and more importantly, the focus should be on investments in education and training, including lower-level jobs. The training of native-born workers, in combination with formal and vocational (on-the-job) training of migrant workers, remains the best remedy to address skill shortages in the labour market, whether they are due to exogenous factors – as in the historical case study – or have a domestic cause.

Further reading

Berkhout, E., A. Heyma and S. van der Werff, De economische impact van arbeidsmigratie: verdringingseffecten 1999–2008, SEO-rapport nr. 2011-47 (Amsterdam 2011).

Berkhout, E., P. Bisschop and M. Volkerink, Grensoverschrijdend aanbod van personeel: Verschuivingen in nationaliteit en contractvormen op de Nederlandse arbeidsmarkt 2001–2011, SEO-rapport nr. 2014-49 (Amsterdam, 2014).

Lucassen, J. and L. Lucassen, ‘The mobility transition revisited, 1500–1900: What the case of Europe can offer to global history’, Journal of Global History 4 (2009) 3, pp. 347–377.

Lucassen, J. and L. Lucassen, Winnaars en verliezers: Een nuchtere balans van vijfhonderd jaar immigratie (Amsterdam, 2011).

Lucassen, L., ‘Cities, states and migration control in Western-Europe: Comparing then and now’, in: Bert de Munck and Anne Winter, Gated communities? Regulating migration in early modern cities (Farnham, 2012).

Van Lottum, J., Across the North Sea: The Impact of the Dutch Republic on International Labour Migration, c. 1550–1850 (Amsterdam, 2007).

Van Lottum, Jelle, ‘Labour migration and economic performance: London and the Randstad, c. 1600–1800’, Economic History Review 64 (2011) 2, pp. 531–570.

Van Lottum, Jelle and Jan Luiten van Zanden, ‘Labour productivity and human capital in the European maritime sector of the eighteenth century’, Explorations in Economic History 53 (2014) 53, pp. 83–100

Vries, J. de, ‘The population and economy of the pre-industrial Netherlands’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XV 4 (1985), pp. 661–682.

Vries, J. de, ‘How did pre-industrial labour markets function?’, in: Grantham, G. and MacKinnon, M. (eds.), Labour market evolution. The economic history of market integration, wage flexibility and the employment relation (London, 1994), pp. 39–63.

[1] The work underlying this article was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (RES-062-23-3339: ‘Migration, human capital and labour productivity: the international maritime labour market in Europe, c. 1650–1815’). Unless otherwise indicated, all data presented in this paper derive from the data collected in this project.